Reconsidering Career Services: Building relationships between students, alumni, and faculty to drive improved outcomes

This article was originally published by NACE, the National Association of Colleges and Employers.

During the past several years it has become fashionable to question the impact of college and university career services departments, or even if schools need these resources. Should these departments be outsourced? Is student placement really the core competency of an academic institution?

If one considers career services in a vacuum, the argument does have merit, especially with the plethora of online resources to facilitate resume proofing, posting jobs, scheduling interviews, and other “administrative” aspects of the career search. However, having met with thousands of career services departments, academic faculty, students, alumni, and other professionals, I am confident that these departments are not only required, but are vital for the ongoing success of our post-secondary educational system.

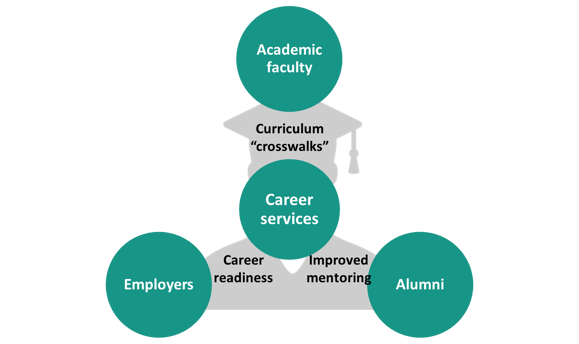

TL;DR: Career services departments are uniquely positioned to serve as the hub of the college or university, using students to facilitate more effective engagement between academic faculty, alumni, and employers. Specifically, career services can:

- (i) support the efforts of academic departments, including articulating crosswalks from curriculum to career;

- (ii) drive improved alumni engagement by facilitating more-authentic mentoring opportunities; and

- (iii) help students and recent grads find the right job and ensure that companies have access to career ready students who are the right fit for their organizations.

The Evolving Role of Career Services

The responsibility of career services has always been to help students get jobs, using tools such as resume books, job postings, interview rooms, and career fairs. However, during the past decade the value of all of these tools has greatly diminished. Resume books have been usurped by LinkedIn; job postings improved with job boards; and interview rooms made more flexible with video conference capabilities. And, as one career services leader said, “I would get rid of the career fair altogether if I didn’t think someone would fire me for it. Standing in line to submit or receive a resume is a waste of time. Employers and students hate them, but we do it because we think we have to.”

Also, career services teams were responsible for making sure that students were effectively prepared for their transition to the real world, with efforts tied primarily to reviewing resumes, conducting mock interviews, and providing career counseling. Historically, these processes took place during junior or senior year when most students were already heavily invested in a given career direction; as a result, while valuable, the resources provided by career services departments were limited in their ability to help students find the “right” job.

The impact of this is evident in the Gallup-Purdue Index, where it found that only one in six grads considered career services to be very helpful. To be clear, this is not the fault of career services professionals, as their departments were viewed as ancillary to those focused on academics and fundraising—in the words of one senior university administrator, they are “little more than project managers.”

Not only does this limit the opportunity for career services to engage with academic faculty, they also faced increasing budgetary pressures. Furthermore, it is worth nothing that these budget pressures disproportionately impact the schools at which students have the greatest need for the support of career services teams as they do not have the backgrounds, networks, etc., to provide the backstop.

As an alternative, instead of thinking about career services as a project manager that engages with students specifically for the transition from college to career, what if we viewed it as the primary interface between companies, alumni, and the college or university? In this role, career services could be the hub not just for campus recruiting, but also as the hub to facilitate continuous interaction between students, academic faculty, alumni, and companies.

Corporate Insights

Post-secondary education is under attack. Almost daily there are articles suggesting that colleges and universities do not need to exist and predicting that boot-camps and micro-credentials will replace diplomas. These conclusions are wrong.

However, while they are wrong, colleges and universities can do better to more effectively prepare students for professional careers. We are not suggesting that academic freedom should be mitigated by corporate programming, nor are we implying that the foundations of liberal arts education should be replaced with vocational training. Instead, we believe that faculty members, students, and companies all benefit when crosswalks between curriculum and careers are highlighted.

Yes, some of this already takes place, especially across classes tied to business and the sciences where “hard skills” are embedded within the syllabus and individual professors often provide examples based upon their research or consulting relationships. However, even in these cases, the insights are limited by the focus of the faculty member. For example, the finance professor whose research focus is tied to market efficiency associated with large mergers is unlikely focused on how this applies for students interested in valuing emerging start-ups. And for departments such as philosophy, history, and literature, the opportunity to provide these crosswalks may seem even more limited as faculty members are typically less connected with the likely employers of their students. That being said, these classes that often have “titles that don’t sound like jobs” require demonstration of the skills most demanded by employers according to NACE research.

In contrast, career services professionals have relationships with employers across industries, roles, company sizes, etc., and therefore access to a perspective that goes beyond what may be available to an individual faculty member or department. Through ongoing discussions with companies, career services understand the demands of employers across departments, and the level of preparedness of the school’s graduates.

And given the NACE report, we know that the skills most in demand are not related to any one course, which means career services is best positioned to provide insights to academic faculty on those gaps and opportunities.

Furthermore, as intellectually curious individuals, academic faculty members are often interested in exploring new areas both for the classroom and research. Given the limitations of their personal networks and expertise, career services can provide a diverse platform of insights and emerging trends that would otherwise be unavailable to a single professor or department.

For example, a philosophy professor may not be aware of how technology companies are using Karl Popper’s theory of falsification to drive marketing strategies, therefore missing out on opportunities to incorporate these examples during lectures—content that could improve both academic and career outcomes for students. And for students who worry that their major doesn’t sound like a job title (“I don’t see any companies with open philosopher roles.”) these things help them see the links between curriculum and careers, thereby driving improved engagement, academic outcomes, and career success.

Alumni Engagement

Having been out of college for more than 20 years, most of my interactions with my alma mater have been limited to letters and e-mails asking me to write a check. Yes, there are events and the occasional sports announcement (go Hoosiers!), but the reality is that the school is most interested in me making a donation. To be clear, I have nothing against this, especially since the alumni relations team has been limited by the arrows in its proverbial quiver.

Alumni relations and career services departments may collaborate to request participation in on-campus recruiting (though I am shocked by how frequently there are “turf wars” around this), but even this is focused on making an “ask” of the alum.

Instead of focusing on the ask, what if alumni relations used insights provided by career services to focus on helping the alum? Career services is uniquely positioned to understand the needs of specific companies, industries, roles, etc., and can use these insights to help craft alumni engagement opportunities that provide immediate value to an alum. For example, alumni relations may not know that a financial services firm is having difficulty competing against emerging start-ups for tech talent, or that tech firms are increasing their efforts to find liberal arts students. Using these insights, alumni relations can develop targeted outreach efforts focused on helping alums in roles or at companies facing those issues. By leveraging the insights from career services, alumni relations can better engage alumni with bespoke solutions such as targeted networking events, micro-internships, and guest lecturing opportunities, all of which help alums build authentic relationships with students to address their needs.

As a result, when the school does make “the ask,” the alum feels more engaged and is more inclined to give.

Authentic Mentoring

The other big ask of alumni is often their willingness to provide mentoring. During the past several years, colleges and universities have spent record amounts on alumni management systems with features that go beyond those of social and professional networks (e.g., contact information, job boards, event management, etc.). In fact, based on discussions with hundreds of alumni relations professionals across schools, mentoring features were a top influencer of how they selected their alumni management software.

Unfortunately, irrespective of the platform and its features, all of these tools have the same fatal flaw: students do not know what to ask. Yes, they all have the standard list of questions, but (spoiler alert) there is no “typical day,” “our company encourages a strong work/life balance,” and “there are plenty of great opportunities for those who work hard.”

Furthermore, having spent considerable time on these types of calls, these conversations also cover topics that should not be relevant to a student (my responsibilities are nothing like that of a recent grad) or focus on information that could be found elsewhere (visit the website to see open positions). The reality is that every alum understands what the students really want to know: “Will you hire me or do you know someone who will?”

To be clear, this is not the fault of the student or school, but rather the fact that there are often no points of connection other than the alma mater.

However, career services can also help solve this issue given its understanding of where more “tactical mentoring” can benefit both students and employers. Instead of the standard conversations that frequently take place, career services can facilitate targeted conversations that leverage the unique perspective of a specific mentor, not only benefitting the student, but also making the mentor feel valued. For example, career services will have insights about the philosophy student looking to break into technology, and can therefore structure a mentoring conversation with a technology professional who is having difficulty recruiting computer science majors. As a result, these conversations are mutually beneficial (and a lot more interesting).

The Takeaway

Colleges and universities should neither think of career services as an independent entity exclusively responsible for getting students jobs, nor should they consider this outside of their core competency. Instead, institutions need to recognize what career services brings to the table about insights that can support experiential learning, opportunities for increasing alumni engagement, and resources to ensure career success for all students. Through these types of efforts, conversations questioning the value of post-secondary education will cease.